ZL8RI Kermadec Island DXpedition – May 1996

Raoul Island is the largest of the 15 islands which make up the Kermadec group, 1000 Km off the northern tip of New Zealand, midway between Auckland and Tonga. Raoul is the 3000 hectare northernmost island in the group, with sea cliffs soaring up to 250 metres. It is a live volcano: wisps of steam still rise from a gaping caldera in the centre of the island. The last eruption occurred in 1964 when black mud, steam and rocks shot up 8km. Earthquakes, one as recently as a year ago, still scare the pants off the few DOC officers who live permanently on the island.

Major DXpeditions don’t just happen. They take about as much organisation as a NASA space flight, and cost almost the same! A rumour that an expedition to the Kermadecs was in the planning stage surfaced in late 1994.1 put my name forward. My first meeting with organizer Ken Holdom, ZL2HU, confirmed that he was a ‘detail man’ and a very skilled administrator. He had plenty of experience in dealing with government departments. The Department of Conservation (DOC) was demanding passports, dictating terms, and offering very little. During 1995, the hundreds of letters on file were testimony to Ken’s dogged determination and belief that he was going to make it happen. By late 1995, the DOC was eagerly offering us facilities on the island (at a price) and couldn’t wait to issue permits, providing they could be convinced we wouldn’t be smuggling wild and exotic flora and fauna off the island. The Radio Frequency Service eventually issued the call ZL8RI, and the other government departments all capitulated in time. The team firmed up as Ken Holdom, ZL2HU; Ron Wills ZL2TT; Lee Jennings ZL2AL; Chris Hannagan ZL2DX, Al Hernandez K3VN, and Bin Tanaka JA3EMU. Peter Watson ZL3GQ, joined us two months before we left. Between us we had over 220 years of amateur radio experience.

Financing

Obtaining $45,000, a ship, generators and five drums of diesel were the major problems. Operating gear, computers, antennas and food were another. Hundreds of letters went out to DX clubs worldwide. 19 Financing a major DXpedition is like collecting money for charity: climbing K2 would have been easier! But, as time went on, finances were looking ‘possible’ by late 1995. Top class organizations like the international DX Association, the Northern California DX Foundation, the RSGB, the Chiltern DX Club the UK DX Foundation, European DX Foundation), the LADXA, Norwegian), the Clipperton DX Association (French), the Danish DX group, the JA DX Group, and other small clubs worldwide promised finance. This was because Raoul was the number one most wanted DXCC country in Europe. The Kermadec Islands were also much wanted for the RSGB IOTA Awards. Individuals who needed ZL8 helped with some amazing donations. March 1996 brought the news that Yaesu and the Nagara Antenna Company would help generously with equipment (see Table 1) and QSLs. We all heaved a sigh of relief and planning took on a new urgency. ZL8RI was rapidly becoming a reality.

Departure

The full team assembled in Hastings, NZ, on April 28 for the last few frantic days of checking, procuring missing items and making last minute changes to the gear. Cutting coax lines, checking connectors and packing radios in waterproof plastic wrap was completed. Simple things like forgetting a pump for the drums of diesel fuel could prove embarrassing. There is no hardware or electronics emporium on Raoul Island. The morning of April 29 saw us begin to load the Evohe at the port of Napier, near Hastings. It was a 25m, two masted, steel-hulled motor sailor ketch with all the latest Sat Nav equipment on board. The yacht can accommodate seven crew and 14 passengers and has sailed to all parts of the globe. Safety was our concern and the Evohe met our requirements easily. At 1.30 the following afternoon, after frustrating passport, customs and fuelling delays, we departed.

The Voyage

After four hours at sea the weather turned bad and most departed the decks and went below. A day later we were 220 nautical miles out in rough seas with l0 foot waves, the bow pitching l5feet, and the yacht rolling 30° in a following sea. And then it got worse. A simple exercise like walking from your bunk to the main cabin was fraught with danger. The offer of dinner brought polite refusals from all of us. Most of the team ranged in colours from a whiter shade of pale to a nice puce bordering on green. Most lost weight. Occasionally, between the northerly storms and fronts we sailed through, a lull saw Al and Chris operating the IC-735 which was part of the yacht’s radio gear. Some good DX was worked, but more importantly we were able to communicate with ur ZL friends who excelled in keeping our families informed. With each degree of latitude decrease it got warmer – and the seas got rougher. Sleeping in the forward bunks was impossible with your bed disappearing 8m below you in a few seconds, followed by the same rise which compressed one’s stomach with the G-force of a stunt pilot’s aircraft. The rest of the trip to Raoul Island was more of the same.

Arrival

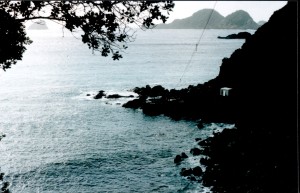

Suddenly it was over. Raoul Island appeared like a dark cloud on the horizon early in the morning of 4 May. The officer in charge of the DOC on Raoul was contacted on marine VHF for assistance in getting ashore. We moored at Fishing Rock which has a gantry crane and ‘flying fox’ (see photo). We surveyed this dormant but active volcano and it became obvious why landing is so difficult. Rough seas, rocky beaches, difficult access and a daunting 300m cliff face to climb presented major problems.

The procedure for landing was to unload the gear out of the ship’s hold and into a Zodiac boat, race the Zodiac to shore with the gear in cargo nets, and make a flying pass at the crane hook. Snag the net full of gear on the hook as the Zodiac pitches up and down metre or so in the swell. Dodge the load as the crane winches it up and swings it around on to the rock. Load the gear on to the flying fox and watch it disappear to the top of the cliff. Unload the gear from the net and on to a large trailer pulled by a tractor and drive the load 3km to our operating site. The next 24 hours were spent installing the station. Two tribanders, a WARC duo bander and four verticals went up without mishap. Slingshot Al’, K3VN, used his device with deadly accuracy to place lines over the huge Norfolk pine trees just outside the operating shack which were used to hoist up the huge delta loops. Bin, JA3EMU, produced an antenna analyzer out of his toolkit and pronounced that the systems would work.

The procedure for landing was to unload the gear out of the ship’s hold and into a Zodiac boat, race the Zodiac to shore with the gear in cargo nets, and make a flying pass at the crane hook. Snag the net full of gear on the hook as the Zodiac pitches up and down metre or so in the swell. Dodge the load as the crane winches it up and swings it around on to the rock. Load the gear on to the flying fox and watch it disappear to the top of the cliff. Unload the gear from the net and on to a large trailer pulled by a tractor and drive the load 3km to our operating site. The next 24 hours were spent installing the station. Two tribanders, a WARC duo bander and four verticals went up without mishap. Slingshot Al’, K3VN, used his device with deadly accuracy to place lines over the huge Norfolk pine trees just outside the operating shack which were used to hoist up the huge delta loops. Bin, JA3EMU, produced an antenna analyzer out of his toolkit and pronounced that the systems would work.

On the Air

It had been agreed that the first QSO belonged to Ken, ZL2HU, so at 0410 on 5 May 1996, ZL8RI on Raoul Island was on the air with a major operation. We tried to prepare Ken for what some of the more experienced members of the team knew would happen when he called CQ on 14195 KHz. He made the call, released the VOX and stared at the radio in disbelief when he was ‘jumped on’ by about a thousand screaming voices. AA2GQ was the first in the log. Ken worked a few more, turned the mic over to Al, and was visibly shaken by his first encounter with serious pileups. Five minutes later we hit the packet clusters and all hell broke loose. It was hour after hour of adrenaline pumping ham radio at its best. CW rates approached 200 per hour whilst SSB rates soared over 275. Hour after hour it went on, and still they kept coming. The first day showed nearly 5000 QSO5 in the log. Peter and Bin took over the RTTY and CW operations on the low bands with great success. During the last weekend of ZL8RI, the Volta RTTY contest was on and we were very popular indeed. Bin spent the evenings on 160 and 80m trying to give vital low- band contacts to as any as possible amongst appalling QRN. Many Ws, JAs and VEs were worked. Operators settled into daily routines. Some enjoyed the night work. The division between day and night became blurred. Sleep was difficult with the noise of generators and QSOs ringing in our ears. I have a small electronic alarm clock which emits a repeated “dit-dit-dit-dit” when it goes off. One night, when it went off at 2.00 am to remind me of my late shift, I awoke with a fright, mentally looking for S55H.

Working DX

The Europeans peaked from midnight until 4.00 am local time on 20m and I used that opportunity to give them some joy. Europeans were difficult to work at the best of times. Some countries in particular thought that the best way to work DX was to find the centre of the pileup, run as much power as possible, set the keyer to 40WPM and let loose. They did not fare well with us. QSO rates dropped to 50-75 per hour, but we persisted because we tried to give every area in the world a fair share. The totals kept counting and our chart showed that we could achieve our goal of 30,000 QSOs

(Table 2). Then, early on 12 May, Murphy struck. One of the two generators died. Within a few minutes, all unnecessary power drain was cut, some linears were turned off and we reduced to three stations. Within 24 hours one of the tribanders developed trouble. The team pressed on and totals still rose, but it was obvious that Murphy could not be tempted again. We had to be off the island by 14 May. During the preceding day, all non essential equipment was repacked ready for the trip home. The last QSO was with UR3LCH.

The Return Voyage Home

At daybreak the team worked feverishly at taking down the antenna systems and loading the trailers ready for the trip back to Fishing Rock and the gantry crane. DOC staff arrived at 10.00 Am and started moving the tons of equipment. We said our goodbyes and set sail for home. Most of the team went below for some much-needed sleep, the first long stretch in two weeks. We awoke to worsening weather with southerlies coming from the Antarctic and up the east coast of New Zealand. The yacht was rolling and pitching again, even worse than the journey to Raoul, with huge seas, 40-50 knot winds, and angry white frothy spray blowing off the top of mountainous waves. About 30 hours before our ETA at Napier, one of the two diesel engines failed. Our speed was slashed to 4.5 knots and the voyage from hell was extended by 15 hours. A few hours out from Napier, the seas calmed and went flat, the sun come out and we went up on deck again. Eight days sailing and we were able to spend a total of only seven hours on the deck to enjoy it. We were home safely and had accomplished what we set out to do.

Band Totals

l60m 300, 80m 2300, 40m 5200, 30m 1300, 20m 10,500, l7m 5000, l5m 800, l2m 1600, l0m 900. Total 33,900 Mode Totals: l3,800 CW, 19,100 SSB, 1000 RTTY 20

Equipment List

Yaesu: FT1000D, FT-1000MP, 2 x FT-900, FL-7000 amplifier Heath SB-220 amplifier, SB-200 amplifier Icom IC-2KL amplifier Nagara tribander and WARC-band duobander Cushcraft tribander, R4B vertical Create 10- 40m vertical, l6Om vertical 80m / 40m delta loops MFJ-982 Versa-tuner x 2 Bencher addles Laptop computers x 6, IBM 286 clone, CT logging program by K1EA, 5kW diesel generators x 2 Teddy bear mascot (Ron’s)

Department of Conservation

Without the advice of the New Zealand DOC staff, ZL8RI would not have happened. The DOC team on the island also taught us much and we could not have done it without them. The gear supplied by Yaesu (see Table 1) worked flawlessly. The FT-1000MP was a joy to use, the best radio I have used in 44 years of ham radio. The new Collins mechanical filter in the FT-900 offers great selectivity and reminded me of my old Collins 75S3 with CW selectivity that goes on forever. The Nagara antennas worked extremely well. Their WARC duobander would be a worthwhile addition to any antenna farm. The Create 10m – 40m vertical worked better than our 40m delta loop. The Cushcraft R7 loaned to us by Ham Radio Direct in New Zealand also worked very well. INDEXA and NCDXF helped us considerably with finances. We are extremely grateful for their help. Thanks to all the organizations and individuals who put their money on the line and put their faith in us. And yes, we are thinking about the next one.

By Lee Jennings ZL2AL – Published in QST, CQ, RSGB, JA Magazine during 1996

2012: 16 Years have passed and sadly Ron Wills ZL2TT and Peter Watson ZL3GQ have become Silent Keys. We remember them and the good times we had on Raoul Island