The star of CBS-TV’s ‘Eye on New York’ Bill Leonard reports on a hobby; amateur radio, that is distinguished by one of the most gruelling international competitions in all sport.

On the night of February 7, 1958, a few moments before 2 a.m., Canadian Army Sergeant Elvin Veale of the U.N. Emergency Force stepped out of his quarters into the bitter night air of the Gaza Strip. He was tense, excited, braced for the job ahead. At the same moment, in a Tokyo suburb, Haruo Yoneda, a Japanese TV executive, pushed back a final cup of breakfast tea and disappeared into the tiny room from which he emerged 48 hours later, glassy with exhaustion, and utterly happy.

Sergeant Veale, Mr. Yoneda, Ludvik Kloucek of the Mongolian People’s Republic, Empty in Johannesburg, Eva and Alex in Casablanca, Nose in Hawaii, this reporter and a multitude of others—from Pitcairn Island to Punxsutawney, Pa.—were about to begin play in the oddest, toughest and by any standards the most international of all sporting competitions. This was the start of the 24th annual DX contest for radio amateurs of the world, sponsored by the American Radio Relay League.

DX means distance in the abbreviated jargon of hams (amateur radio operators)—and the object of a DX contest is for one station to talk to as many other stations in as many other places as possible in a prescribed length of time. The Grand National of the many DX contests sponsored annually by clubs, organizations and magazines in dozens of countries (including Russia) is the ARRL’s affair. There are more American hams (140,000) than in all the rest of the world combined (60,000), and in this biggest of electronic scrambles operators in the U.S. and Canada compete against each other and talk only to foreign stations.

Overseas hams contact only Americans and Canadians. It takes about six months before logs, sent from the six continents, can be tabulated and checked. So this year’s winners won’t be officially known until the results are published in an early autumn issue of QST, the official magazine of ham radio. But on the basis of claimed scores, still subject to cross-checking, George Morrow, W8BKP, of Washingtonville, Ohio, and Robert Cheek, W3LOE, of Catonsville, Md., may be the U.S. high scorers for voice and code respectively. Outside the U.S. Katashi Nose, KH6IJ, of Hawaii swept both the voice and code contests for the first time ever.

These, and the other winners in foreign countries and various sections of the United States and Canada, cart away no cash or golden wassail cups. Certificates (suitable for framing—but barely) are the only visible rewards of this tense and exhausting competition. The thrills are not in the prizes or the honors but in a kind of fish-and-hunt excitement, with a voice 6,000 miles away in Rarotonga or Rio de Oro as the quarry.

Depending on just how serious he is on the subject, the DX contest man will not only kill himself in a contest, but he will spend the better part of a year getting ready for the exquisite torture of 48 hours of almost continuous operating. He will plan, assemble and erect, usually at considerable cost and occasional risk of limb, an endless succession of antennas, designed to make his station sound just a little louder in Minsk than the fellow who beat him out last year. He will memorize (if he doesn’t know them all to begin with) the names and call-letter prefixes of every “country” in the world (there are nearly 300 “countries,” for hams count many islands and possessions as well as motherlands). He probably has written or talked previously on the air with a hundred hams half a world away arranging crucial schedules for the contest period. He has experimented with diet and sleep habits, stay-awake pills and coffee strengths and has literally gone into training for the contest ordeal. He does all these things and, in addition, takes a lot of perfectly sensible abuse from what are laughingly referred to as loved ones, because ham radio in general, and a DX contest in particular, is more fun than beating Yale. It may indeed be true that while golf is a game, bridge a hobby and girls an avocation—ham radio is a passion. Like most passions, it is pretty much a mystery to those who are not in love.

Amateur radio, like the airplane, is no longer a crude Kitty Hawk baby. Once it did take a garage full of fairly frightening equipment to say almost nothing to almost nobody almost no distance away. And it took an odd breed of nose-in-the-formula duck to master the intricacies of the spark gaps, tickler coils and reflex audions, to say nothing of the dots and dashes. Today, a transmitter-receiver combination no bigger than a portable typewriter is on the market, easily capable of regular communication with all parts of the world. It is about as difficult to operate as a home hair-rinse kit.

A great deal has been written about the work of hams in national and local emergencies—floods, wrecks and hurricanes. Hams are proud of their public-service record. Perhaps just as important, and frequently overlooked, is the fact that hams are among the nation’s best ambassadors abroad. An estimated 10,000 conversations between U.S. and foreign hams take place every day. The Voice of America considers ham radio of such vital international interest that one of its few programs in English, beamed to Europe and Asia, is a weekly ham show.

There are hams who are housewives (girls allowed) and bandleaders (Gene Krupa), politicians (Herbert Hoover Jr.) and comedians (Arthur Godfrey), kings (Prince Abdullah Feisal of Saudi Arabia) and writers (Ernest Sweet Smell of Success Lehman), ship captains (Kurt Carlsen of the ill-fated Flying Enterprise) and captains of industry (Hazard Reeves, president of Cinerama), guardians of the air (Air Force Vice-Chief of Staff, General Curtis LeMay) and of the seedy (New York Prison Warden Ed Dros). There are hams who are doctors, lawyers, and a sprinkling of Indian chiefs, in India.

Of course, every American knows how radio works, just as he understands television, refrigerators, reciprocating engines, women’s minds and other everyday miracles. But we shall risk a word about how amateur radio fits into the broadcasting scheme.

Radio energy can be pictured as waves, all traveling at the same speed, the speed of light (light, incidentally, is just very, very short radio waves, and our eyes a remarkable radio receiver that tunes in on light waves). Some radio waves are long, only a few of them passing a given point each second. Others are short waves, hardly any distance between crests, but many waves passing a given point each second. The wave lengths used for regular broadcasting are quite long (around a quarter mile from trough to trough). TV uses much, much shorter wave lengths, its channels falling in the so called VHF (very high frequency) and UHF (ultra high frequency) range.

Most of the bands assigned to hams fall in the wave lengths in between, where almost all long-distance radio transmission takes place, not only amateur but military, plane to plane, ship to shore, commercial services, international broadcasting and overseas radio telephone. In the range between 10 and 100 meters the radio waves exhibit the remarkable property of bouncing off a vast electrified layer of the upper atmosphere, called the ionosphere, and returning to earth thousands of miles away. It is a tricky business predicting just how and when which waves will bounce how far, for conditions change violently almost minute to minute, according to a dozen factors, including the season of year, light, darkness and sunspot activity.

Hams can operate in seven narrow ranges, the so-called 10, 11, 15, 20, 40, 80 and 160 meter bands where international DX is common. In addition other VHF and UHF bands are set aside for more or less local work. Hams can use either voice or code, the original and still popular dot-dash method of radio communications. There is too little space on the highways of the ether for the great number of stations traveling on them. So the ham at his own station has to contend with the problem of interference from other hams, as well as the never-ending job of keeping his gear in workable shape. In the early TV days neither ham equipment nor television sets were designed to keep the ham signals from interfering. Now, ham techniques and equipment and TV receivers have improved to the point where television interference from amateurs is a steadily diminishing problem.

Actually, ham radio (ham is a 50-year-old corruption and contraction of amateur) is not simply one activity but many. For the competitive, the rigorous contests are available. But just as all motorists aren’t race drivers, so most hams pursue quieter aspects of the hobby. For the tinkerer and do-it-yourself addict there is equipment to put together, tear apart and put together again, equipment handsome enough and complicated enough to satisfy any hi-fi bug.

The gabber gets a chance to talk endlessly on the airwaves, and the listener can eavesdrop to his heart’s content. It’s not unusual for round-table Kaffeeklatsch QSOs to embrace a dozen hams all on one wave length, but located on all six continents. English is the international ham language. English, plus a set of pidgin abbreviations like OM for old man, hangovers from the all-code days when contractions were the natural result of attempts to speed up dot-dash conversations. Also hams use some of the international “Q” signals, which translate, in any language, into key phrases. A QTH is a location; QRN is static.

There is a little of the collector in us all. Hams carry the stamp dodge one better. For many of them it isn’t enough just to have made contact with the remote Russian republic of Uzbek. Who would believe there was such a place? So every ham has his own QSL, or confirmation cards, proof that the QSO (communication) took place. Cards from all 48 states earn a special Worked-All-States certificate. Even tougher is a DX Century Club award, confirmations from 100 countries. A couple of thousand hams have this one, and a handful have cards from 275 countries, which are almost all there are. Another award (issued by the ham magazine CQ) divides the world up into 40 artificial zones, and the trick is to get cards from hams in all of them. Zone 23 is mostly tundra and Tibet, and hams there are as rare as centerfielders. Robert Ford, an R.A.F. radio operator, put Zone 23 on the map, operating from a monastery for a few months eight years ago. Then he was captured by the Communists and became famous as a man who survived five years of attempted brainwashing and Red torture. When he was released in Hong Kong three years ago, the first Westerner to greet him was a British colonel. The officer was a ham first and an Englishman second. He threw his arms around Ford and cried, “Thank God you’re alive, Bob. I’ve been sweating out your QSL card for six and a half years.”

Some hams concentrate on message handling (two New Jersey high school boys have handled over 1,500 telephone patches—relays—for our Antarctica base personnel), others get their kicks out of Civil Defense work and still others use their sets only to keep in touch with one or two friends who are also hams. Just as strangers almost always start to converse in generalities, often inanities, so do hams. The wonder is—and this is the secret thrill of the game—that you can talk at all, that the little black box you built yourself puts your voice and your mind’s eye into the home and the consciousness of a human being who may be a missionary in the Congo, an undertaker in Sweden or a schoolboy in Uruguay. Whoever he is you will call him by his first name, even if—and this has happened countless times—you are an Air Force mechanic and the other ham is a four-star general. You will probably not know, and if you do you won’t care, whether the lad with the outstanding signal on the high end of 20 meters is tall or short, black or white, Democrat or Republican, Jew or Gentile. And any ham can tell you something about the meaning—or lack of it—of national boundaries. The chances are the fellows he likes to talk to most live a day’s flight and a visa away. Through radio they are in his “shack” daily.

To this aficionado, who has been hamming for just a quarter century, and whose shacks have included an airplane over Addis Ababa, a chicken coop in Vermont, a movie house on Broadway and a hotel balcony in Haiti, the ham DX contest is the hobby at its zestiest. The big one just concluded embraced four weekends in February and March—two weekends of 48 hours each for voice operators, two for CW (code) men. There is no law, except common sense, preventing a single operator from working all 48 hours all four weekends. Indeed, the Hawaiian school teacher named Katashi Nose, whose call is KH6IJ, who is this year’s champion, regularly does just that. Along with a Virginian (Vic Clark, W4KFC), Nose is just about the best all-round contest man. He builds his own equipment, including a set of huge antennas on towers he raised and climbs himself. He is equally adept at key or microphone. His endurance seems endless. Favored with a location comparatively close to the U.S., he regularly exchanges contest serial numbers and reports with 3,000 U.S. hams in a single competition. He and Clark, year in and year out, are among the top scorers in the world. The toughest grind is going it alone. The ARRL rules are very strict about single-operator participation. No one else may assist you in any way, either in keeping logs or repairing equipment and certainly not in touching the key or the mike. There is not much more-than the honour system to support the operational rules, although there is a log check on contacts.

A milder version of most DX contest hamming, including this year’s ARRL affair, is so-called multi-operator participation. Here, a group of hams, prizing sleep more than honour, will get together and take turns operating one or more transmitters at a single chosen station. This is equivalent to joining a relay team, instead of going the mile alone. It’s lots of fun, but hardly as demanding.

Perhaps the most elaborate multi-operator station extant is owned by Hazard (Buz) Reeves, K2GL, a superb technician, whose electronic know-how has paid off handsomely in business. He is president of half a dozen successful companies, all with radio overtones. A sizable section of his Tuxedo Park, N.Y. hilltop mansion and surrounding grounds is devoted to a ham station de luxe. Dominating the landscape are two towers, loaded with antennas, both over 100 feet high. The antennas on the towers rotate—squirting the radio signals in favored directions.

The shack is a 30-by-35 upstairs room, dominated by three 1,000-watt transmitters, three top-quality receivers, a room-long workbench, tools by the hundreds, a tape recorder and special operating chairs designed for minimum back strain, in one of which this particular operator collapsed as utterly as if he had stopped a Robinson left hook, at the end of contests in the years when he used to go it all alone.

It was in this luxurious setup that we shared this year’s ARRL contest. Reeves flew up from Florida to join six others for one weekend of high-speed contest fun. Reeves does little operating himself. His kicks come from keeping the maze of complicated equipment in operation. Most of the talking was done by Dick Dorrance, a New York advertising executive; Fred Capossela Jr., son of the noted track announcer; John Ryan, an Anaconda Copper heir, who regularly flies across the continent to operate from K2GL because he considers it the best station in the world; Gene Kern, chief of the New York office of the Voice of America; and David Rosen, a young radio announcer.

In the first half hour of the contest we touched all continents. Signals churned into receivers from Japan, New Zealand, Morocco, Portugal, Argentina and nearly every other nook that man has wired for electricity. Contest contacts are quick—an exchange of identifying reports, a time check, serial numbers, hello, goodbye, that’s all. But there was time to find out that one of our first contacts was operating from a 1953 station wagon in the Argentine pampas.

Four hours on, four off was our schedule, and before the next day had gone we had worked a rare station in Sarawak, British North Borneo. One of the most unusual of all countries is tiny Kermadec Island, 1500 miles off the coast of New Zealand. There is only one ham there, and he operates on a band that usually carries just a few hundred miles. But with a lot of effort and the help of a New Zealand amateur, we made contact with him.

A DX contest score is arrived at by multiplying the number of contacts by the number of countries, working each station only once. But as you operate on a different band of frequencies you can contact the same station all over again for another multiplier. It’s quite a trick to catch the same overseas station on all HF bands; in fact, not two stations in an average year manage to swing it. But luck was with us, and in a single four-hour period we talked to Bill Vrooman, HH2Z, who runs Haiti’s International Country Club resort, on all seven bands.

The thrills piled up, but so did the problems. Sunday morning the rotating mechanism on one of the towers jammed. We operated at something like half-effectiveness, while Buz fixed it in two hectic hours. Toward the end of the contest a power transformer went west. John Ryan figured out a way to make a replacement spare do the job. Somewhere along the line we were inspired to fashion an extra antenna on the off-chance that it might be useful on a little-used frequency. It wasn’t.

At the end of the weekend we had exchanged reports with 600-odd stations in exactly 100 countries, a creditable score, considering we had only participated one weekend out of two. It was far from a record. We had simply had our fun—enough to tire but not exhaust.

But around the world, Veale in the Gaza Strip, Yoneda in Japan, Nose in Hawaii, and a hundred others who had gone it alone staggered red-eyed to their sacks, surfeited with DX, the voices of the whole earth ringing in their battered ears, vowing they would never go through anything like that again. And they won’t. Not until next year—when it’s DX contest time again.

This article was written by Bill Leonard W2SKE (SK) Bill worked for the New York Post back in the 1950s and was a ham for most of his life aside from being an award winning journalist. Many of the icon legends of ham radio in that period are now SKs but their exploits still live on. Little has changed in the amateur radio contest scene since then. The equipment is far more sophisticated, the antennas a bigger and computers control virtually everything in the station. What does remain is the keen sense of competitiveness to win for your section or division or country or internationally. Contesting is an addiction that refuses to go away. It just gets bigger every year.

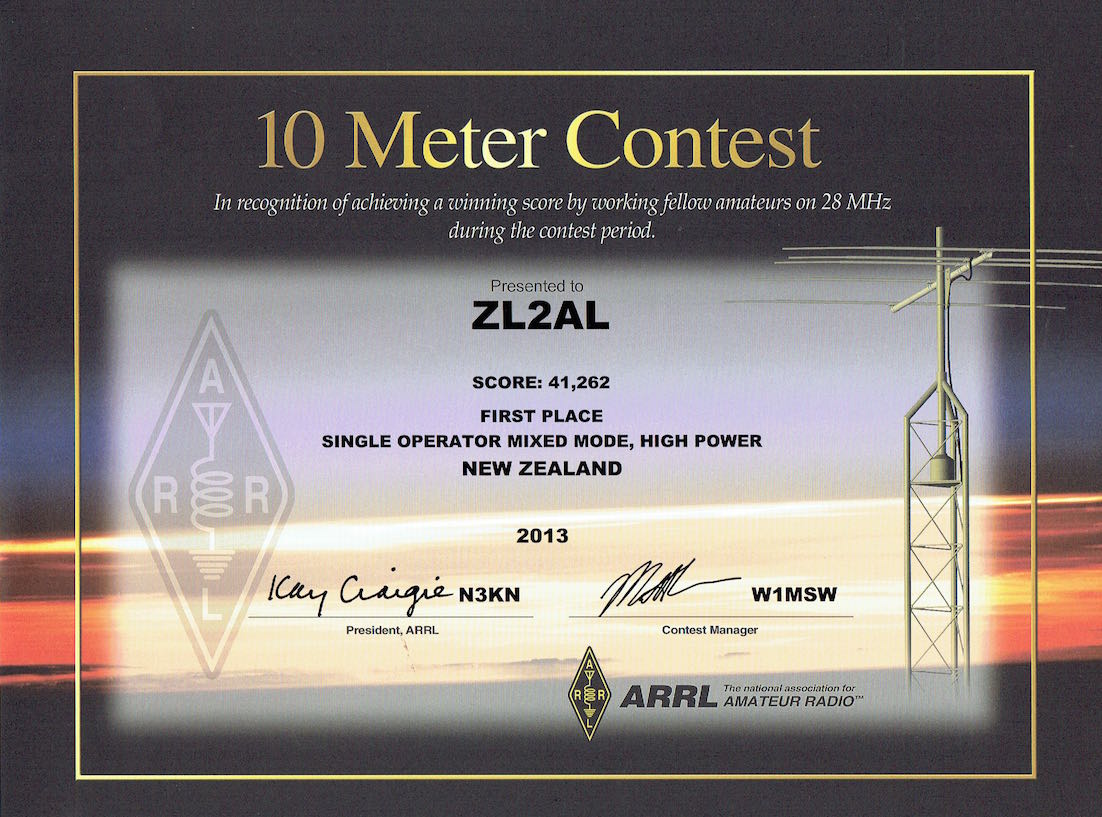

73, Lee ZL2AL

Sep22

Sep22