The IBM 704 Scientific Computer

Magnetic Core Stacks at the Left, Mainframe in the Centre.

727 Tape Drives with the 407 Line Printer at the right

Sometimes truth is stranger than fiction. After leaving college in Toronto I went to work for IBM Canada as an engineer. After a 6 months course at the Don Mills IBM plant in Toronto I left for Ottawa for a 1 year stint servicing the punched card accounting machines that analysed and crunched the data for the 1958 Canadian Census. Punched cards generated big money for IBM. It was the dawn of the computer era and after another few months of training during 1959 I was assigned to the new IBM 704 scientific computer based at the A V Roe plant on the outskirts of Toronto along with 2 other technicians. The A.V. Roe Aircraft Company of Canada was building the Avro Arrow and the 704 was to be used for design work. The aircraft was a revolutionary jet interceptor, designed and built by Canadians. The delta winged Arrow was a plane of firsts: fly by wire, computer control, and integral missile system and capable of MACH 2+. The COLD WAR with the Soviet block was raging.

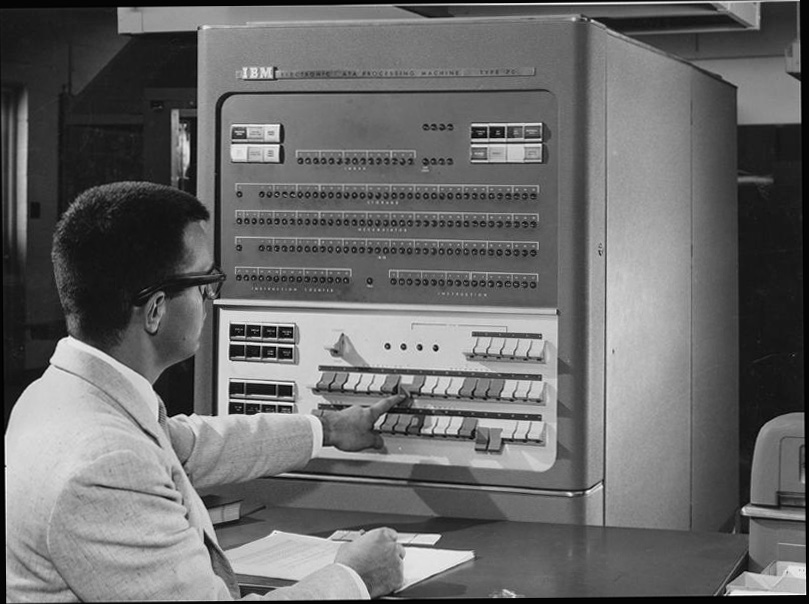

That’s me at the console in the photograph above. I was 23 at the time.

IBM manufactured and sold 136 704s. This one was the only one that ever made it to Canada. The usual method of input to the system was magnetic tape, but entry could also be gained from punched cards through the card reader or from the operator’s console, if special instructions were required. All information, whether part of the data to be processed or part of the program of instructions, started out on punched cards. Then, it either could be converted directly to magnetic tape before being read into the system, or it could be read directly.

At the start of each procedure, the program of instructions was read into the memory from tape or cards and was stored there for use with each record processed. Usually the records to be processed would already have been converted from punched cards to tape or would be on a tape that was the output of an earlier processing operation.

The results of the processing were either produced on a line printer, on a magnetic tape, or on punched cards. If the operator did not want to tie up the entire system while the relatively slow printing or punching was accomplished, he or she could produce an output tape, then connect a tape unit directly to the printer or card punch and print out or punch the results without using the principal components of the system.

It had some massive computing power for it’s time which included 2 x 512 k magnetic core memory stacks, 6 high speed tape readers, punched card input reader and the huge mechanical line form printer on the right of the photo. The tape handlers at the back in the picture were IBM 727s, among the first drives using vacuum columns and tapes made from plastic which was coated with an iron oxide for magnetic storage. These tape drives and, more importantly, the tapes themselves stimulated the acceptance of half-inch-wide, 7-track tape, with recording densities of 200 cpi, and speeds of approximately 60 inches per second (ips) as an industry standard. Additional capacities were added over the years: 556, and 800 cpi, and speeds of 120 ips or more. Each 36-bit computer instruction contained 1 or 2 address fields of 15 bits, so that the full 32K, 36-bit word memory could be addressed directly. The two fields were called decrement (an index) and address, and those names live on in the LISP commands CDR and CAR.

The main console is shown below.

The IBM 704 became the dominant vacuum-tube logic computer in the late 1950’s. A 32K, 36-bit word memory was the largest available. The console is shown below and you could read what was in the memory stacks from the neon bulbs above. You could also input a binary word via the switches below. It was programmed in Fortran language and had a 36 bit binary word as it’s data on the wire buses. Each 36-bit computer instruction contained 1 or 2 address fields of 15 bits, so that the full 32K, 36-bit word memory could be addressed directly. The two fields were called decrement (an index) and address, and those names live on in the LISP commands CDR and CAR.

IBM stated that the device was capable of executing up to 40,000 instructions per second.

The programming languages FORTRAN and LISP were first developed for the 704, as was MUSIC, the first computer music program by Max Mathews.

In 1962 physicist John Larry Kelly, Jr created one of the most famous moments in the history of Bell Labs by using an IBM 704 computer to synthesize speech. Kelly’s voice recorder synthesizer vocoder recreated the song Daisy Bell, with musical accompaniment from Max Mathews. Arthur C. Clarke of 2001: A Space Odyssey fame was coincidentally visiting friend and colleague John Pierce at the Bell Labs Murray Hill facility at the time of this remarkable speech synthesis demonstration and was so impressed that he used it in the climactic scene of his novel and screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey,[2] where the HAL 9000 computer sings the same song.

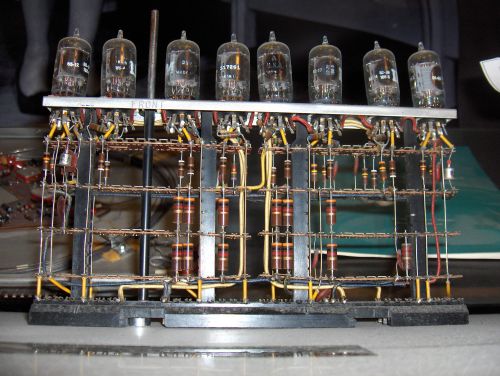

64K Magnetic core memory stacks using physical ferrite “doughnuts” about 10mm diameter which had a X and Y wire pass thru them and a “sense” wire wrapped around the ferrite which would sense the magnetic “flip” caused by the X and Y currents. The ferrite doughnut would then represent a digital 1 or a 0

The magnetic but because of the cost of memory 8K and 16K systems were common. It was the first IBM machine to use core memory. The memory cycle time was 12 microseconds and an integer addition in its registers of 36 bits required two cycles, one for the instruction fetch and on for the data fetch. Floating point operations required on the order of 10 such cycles.

During their tenure, memory capacity grew as IBM learned how to make core memory. Initially, the 704 had 4K, then 8K then 32K words. A word was 36 bits. The 704 was a nightmare to work on. It had 4000 tubes and an 8 Mhz clock with 117 miles of wiring. The tubes were mostly 12AT7s on a “pluggable unit” with 8 tubes on it.

The 8 tube Pluggable unit with “real” resistors and capacitors.

This unit represented 1 “bit” in a 36 bit word in one register

The 4000 tubes ran on on +150 Volt and -150 Volt power supplies with 12 VAC for the tube filaments. Needless to say the machine generated enormous amounts of heat and required 32 tons of air conditioning to keep it a constant temperature. As the engineering technicians, it was our job to keep the machine running. We used to bring up power and get the machine up to temperature each morning at 7 Am and then run a “Round Robin” program which checked out every possible function in Fortran. While it was doing it’s run, our job was to vary the DC voltages until it failed and note where it failed. We then had to return the machine to normal operation and have it ready for an 8 Am customer start. During the day, we poured over manuals and diagrams trying to figure out which tube (or tubes) was failing to cause the problem. At 5 Pm or the next morning we would replace a pluggable unit and check to see whether the problem went away. When it didn’t go away and got worse each morning we all knew that panic was not far away and IBM management took a dim view of the machine not working as it cost them a lot of revenue every hour it was off line.

I was “married” to this 704 computer and was on call any time if required, along with 2 other technicians from 1959 to 1962. When AV Roe in Malton Ontario closed down the Avro Arrow production because of the decision to “can” the Arrow by the Canadian Diefenbaker government we dismantled the whole machine and re-assembled it at the IBM Data Processing Center on Eglinton Avenue in Toronto where we set it up again. It then operated as a data cruncher for an oil company and a University and other commercial customers. I understood that IBM rented it out at thousands of dollars an hour. Demands for computing were growing rapidly and the world was well over tubes and into transistors. Solid state was the word! I started to work on solid state equipment and then decided to leave IBM after 7 years to work for Canadian Motorola. I didn’t realize it at the time, but it was the greatest privilege to be able to be there at the dawn of the computer revolution. Yes, Bill Gates and Steve Jobs did some cool stuff in the 1980s and the urban myth is that it was the beginning. It wasn’t!

IBM was the beginning and for 20 years they dominated the industry with the 700 series, 650s, 305 Ramacs and other commercial computers. Sadly, they never saw Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and others of their kind coming and IBM lost it’s whole business base to the silicon valley upstarts. The IBM empire slowly crumbled and changed. It became a mere shadow of it’s former self. Interestingly, both Microsoft and Apple are trying to stay on top today as IBM did back then. I wonder if in 30 years time I would be able to write the same story about corporate arrogance and incompetence. In any case. it was the end of an amazing era. Working for IBM was a privilege. It was a time in history and a chance for me that will never happen again. I am still amazed that I was part of that continuing story of the computers.

Leith Jennings

Pingback: Visto nel Web – 112 | Ok, panico

Great article. I especially enjoyed learning where Lisp car and cdr came from. Thank you.

My first programming was in Intercom 500 and Machine Language on another vacuum tube computer, the Bendix G-15. It had the strangest instruction set I have seen in 50 years–I started programming as a freshman in college in 1963. I am familiar with the early IBM mainframes also, as we used Purdue’s 7094. I later transferred to Purdue where I got a job helping program for EE grad students. I am currently working on emulators for these early computers — the simple ones such as the LGP-21/30 series are good teaching aids for machine language concepts.

Good memories of a fabulous era in mankind’s great leap forward in the world of computing. The 704 and 709 were sisters and the 7094 was the next development up and then they went solid state. Thanks for the comments